Please read this introduction first before looking through the solutions. Here’s a quick index to all the problems in this section.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

To aid in solving problems in this section I recommend reviewing conic sections1 and their equations in the standard form and the General Cartesian form.

For those who don’t have the book at hand, here are the details of Example 1.

- The viewing point, , is the point .

- The picture plane is the plane .

- The plane containing the scene is the plane .

- is the circle .

- The image of is the ellipse .

- The , system is the plane and the , system is the plane.

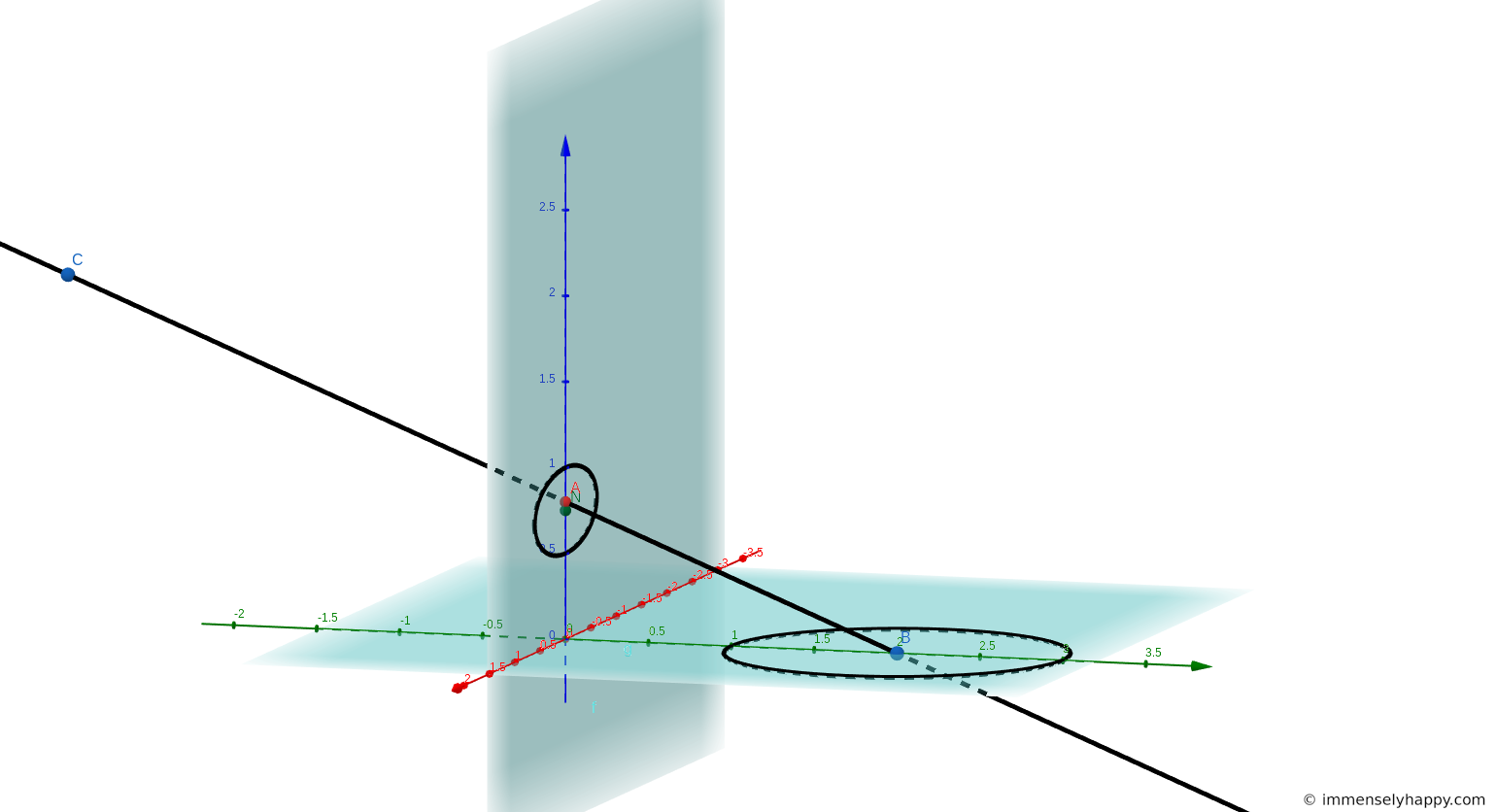

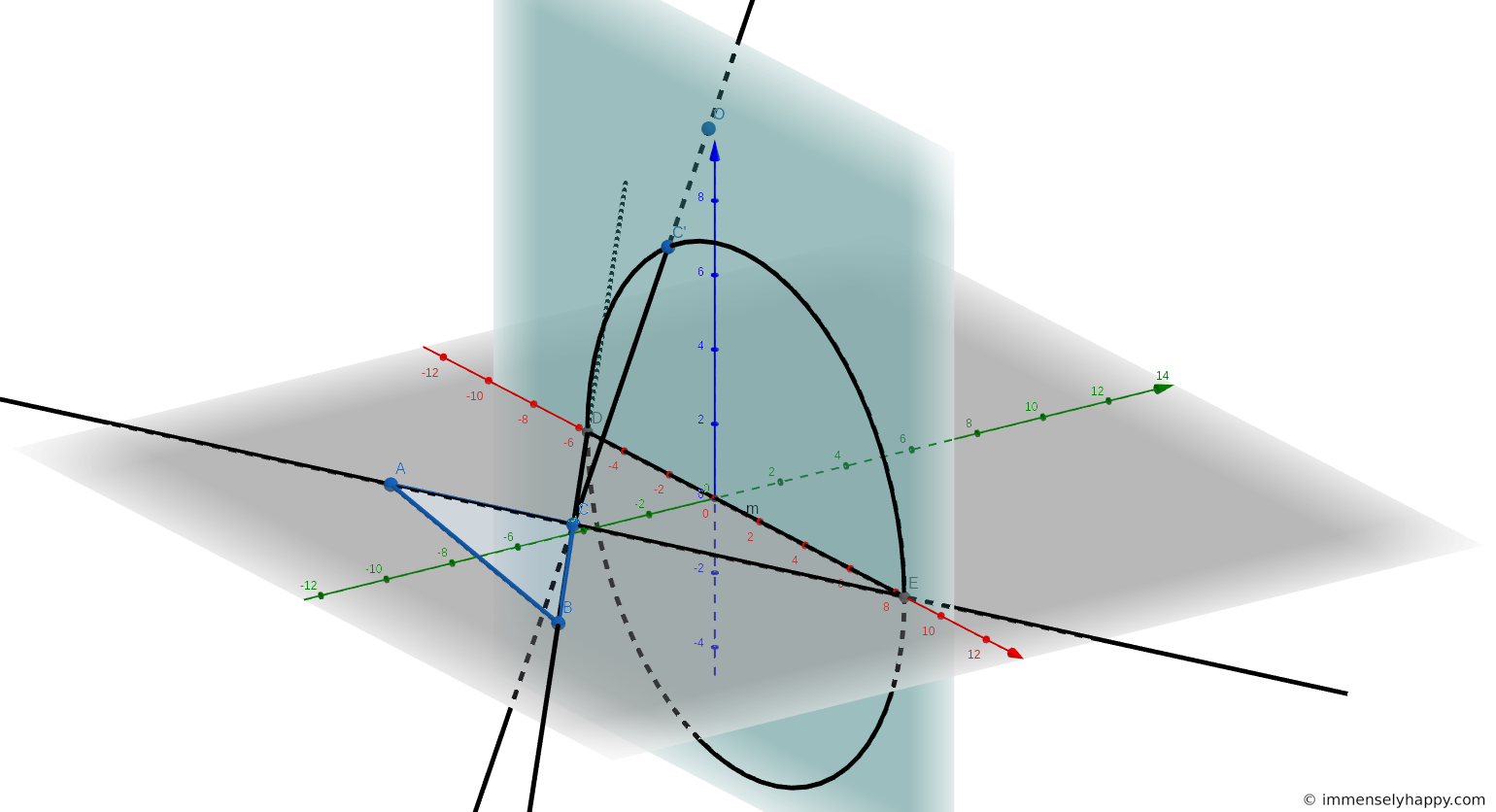

1. In Example 1, does the center of the ellipse which is the image of coincide with the image of the center of ?

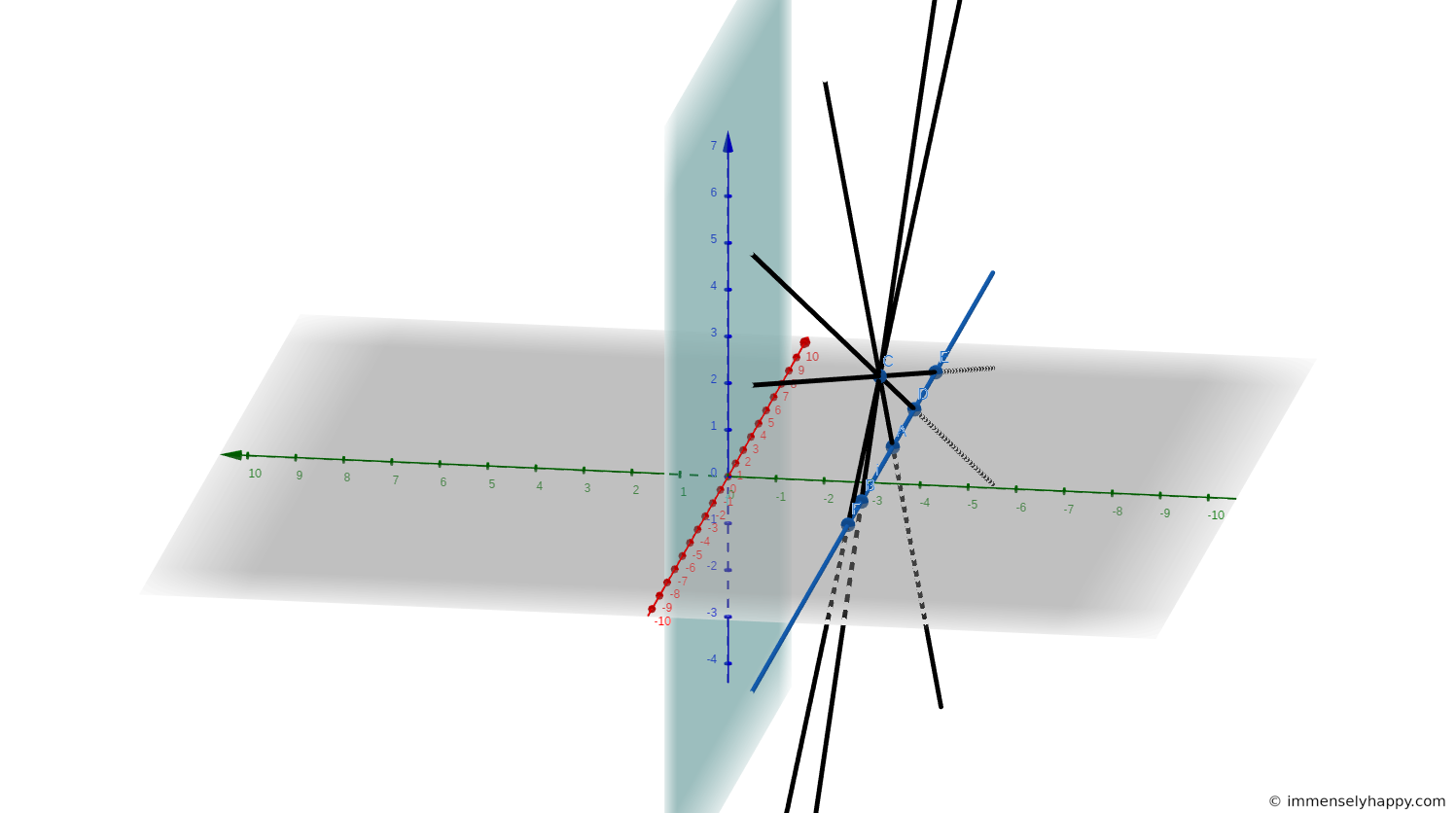

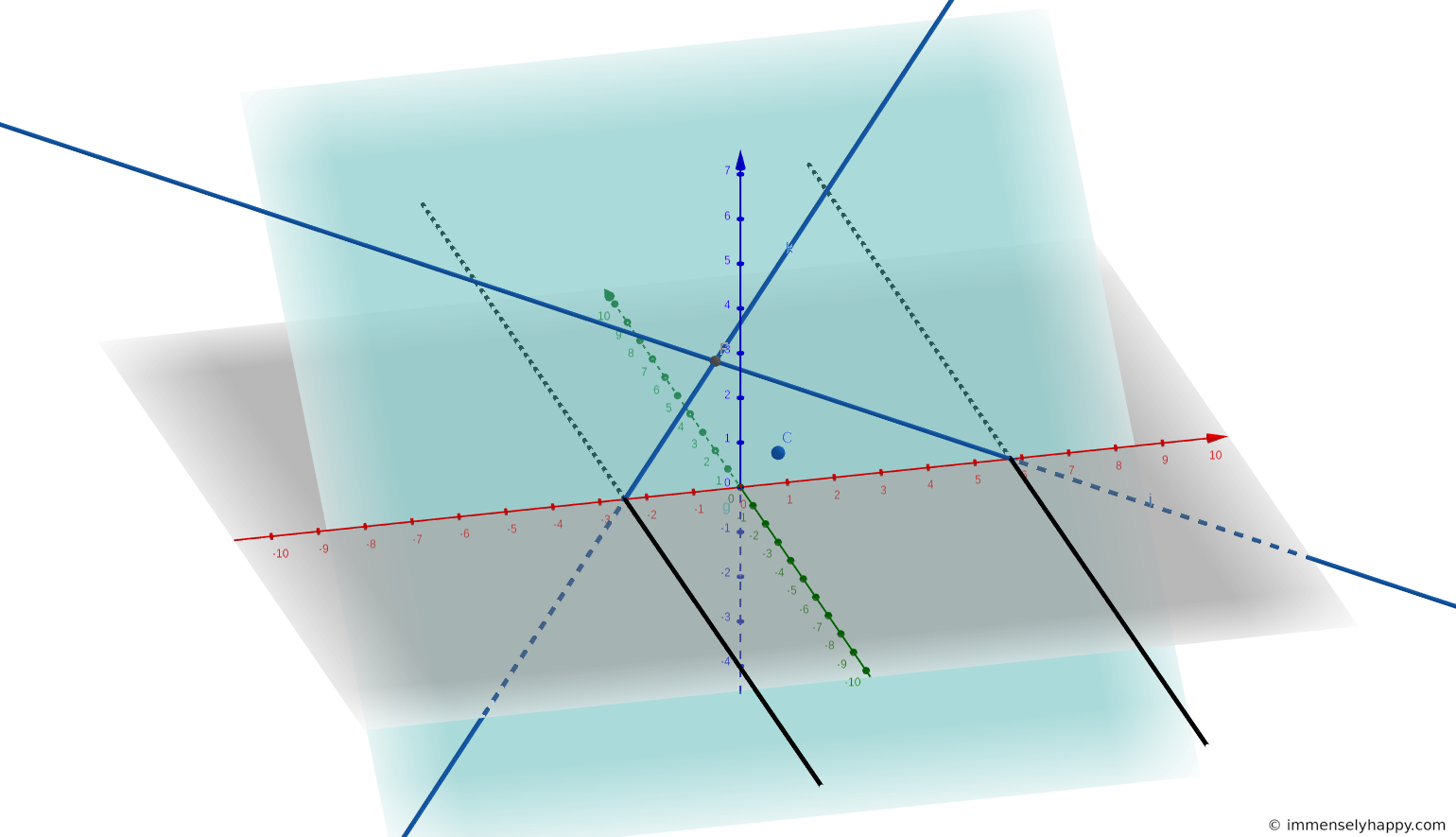

As you can see from the construction of the perspective transformation below, the image of the center of the circle just misses the center of the ellipse .

You can also verify this using the equations of projection derived in Example 1.

Thus A has coordinates .

The ellipse’s center can be found by converting the equation in the General Cartesian form to the standard form. So

can be rewritten as to get the center of the ellipse as . Thus it is clear that and do not coincide.

Note: I have double checked this answer and I think the answer in the book should be instead of .

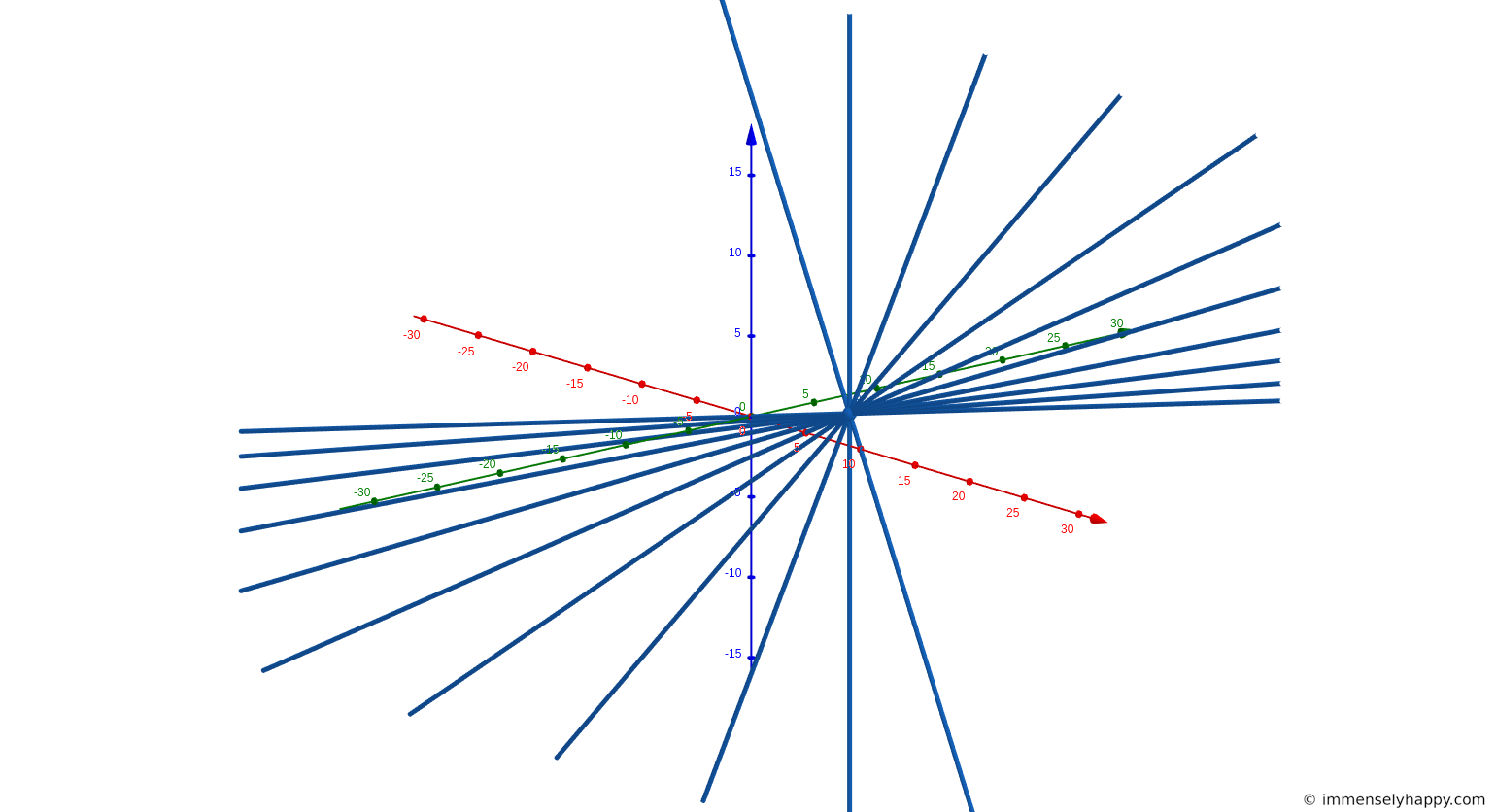

2. In Example 1, what is the image of the family of parallel lines defined in the object plane by the equation ? By the equation ?

To find the image of the family of parallel lines defined by , we substitute and with their expressions in terms of and as derived in Example 1, in the equation for the family of lines. This gives us

For all values of this line passes through and which is a point on the vanishing line , as required by Theorem 2 (Page 7).

The image of a family of parallel lines under perspective transformation in general is a family of lines passing through a point. In this case, the point is A . If you’re viewing this in GeoGebra, hit the play button next to the slider variable to view the lines being drawn one-by-one.

Similarly, the image of the family of parallel lines defined in the object plane by is given by

As this family of lines must pass through the vanishing line in the picture plane, it must pass through . Solving for we get . So the image of this family of parallel lines must pass through , .

In the special case that , the family of lines is parallel to the x-axis. The images of these lines, , are also parallel to the x-axis. The x-axis is common to both the picture and object plane. So lines in the object plane that are parallel to such a common line, have images that are also parallel; their images do not converge to the vanishing line in the picture plane.

3. In Example 1, what is the image of the parabola whose equation in the object plane is ? What is the image of the parabola whose equation is ?

Rewriting and in terms of their coordinates on the picture plane we get the image of both the parabolas as follows.

For parabola , we have

This is the equation of an ellipse in the standard form with center at , and axis lengths 2 and .

For parabola , we have

This is the equation of a hyperbola with center at , and asymptotes .

Isn’t it surprising to see a parabola looking like an ellipse and even a hyperbola depending on where you view it from? This made me acknowledge the reality of different perspectives and that my reality is no less right (or wrong) than another person’s take on a situation.

In a later section we will learn the specific conditions under which a parabola’s image will become an ellipse, a parabola and a hyperbola respectively.

4. Rework Example 1 if is the point .

The equation for the projecting line PC, passing through a general point on the object plane and the viewing point , is

To find the coordinates of the point in which this line pierces the picture plane, we need to substitute and solve these equations for and , getting

Thus the image of the given point is or

To find the image of the family of parallel lines defined in the object plane by the equation , we first express and in terms of and , getting

Then we substitute this in the equation of the line to get

Thus the image of the given family of parallel lines is the family of lines passing through the point .

To find the image of the circle, we again substitute the expression of object coordinates in terms of image coordinates in the equation of the circle to get

which is the equation of an ellipse in the General Cartesian form.

5. Rework Example 1 if the picture plane is the plane .

Taking the equation of the projecting line PC from the book, we get

To find the coordinates of the point in which this line pierces the picture plane, we need to substitute and solve these equations for and , getting

Thus the image of the given point is or ! This point lies on the intersection of the picture plane and the object plane, and hence is invariant under the given perspective transformation.

To find the image of the family of parallel lines defined in the object plane by the equation , we first express and in terms of and , getting

Then we substitute this in the equation of the line to get

Thus the image of the given family of parallel lines is the family of lines passing through the point .

To find the image of the circle, we again substitute the expression of object coordinates in terms of image coordinates in the equation of the circle to get

which is the equation of an ellipse in the General Cartesian form.

6. Rework Example 1 if is the point and the picture plane is the plane .

The equation for the projecting line PC, passing through a general point on the object plane and the viewing point , is

To find the coordinates of the point in which this line pierces the picture plane, we need to substitute and solve these equations for and , getting

Thus the image of the given point is or

To find the image of the family of parallel lines defined in the object plane by the equation , we first express and in terms of and , getting

Then we substitute this in the equation of the line to get

Thus the image of the given family of parallel lines is the family of lines passing through the point .

To find the image of the circle, we again substitute the expression of object coordinates in terms of image coordinates in the equation of the circle to get

which is the equation of an ellipse in the General Cartesian form.

7. In a perspective transformation, are there any points which coincide with their images?

As we discovered in problem 5, the points on the line of intersection of the image and object planes coincide with their images. The line through the viewing point intersects both the planes at the same point everywhere on this line. There is another special point that is invariant but as it is explained in detail in the next section, I will not go through it here.

8. In a perspective transformation, is every point in the picture plane the image of some point in the object plane? Does every point in the object plane have an image in the picture plane?

Consider the line of intersection of the picture plane with the plane parallel to the object plane passing through the viewing point. The projecting line for a point on this line will never intersect with the object plane. Hence the points on this line are not the images of any points in the object plane.

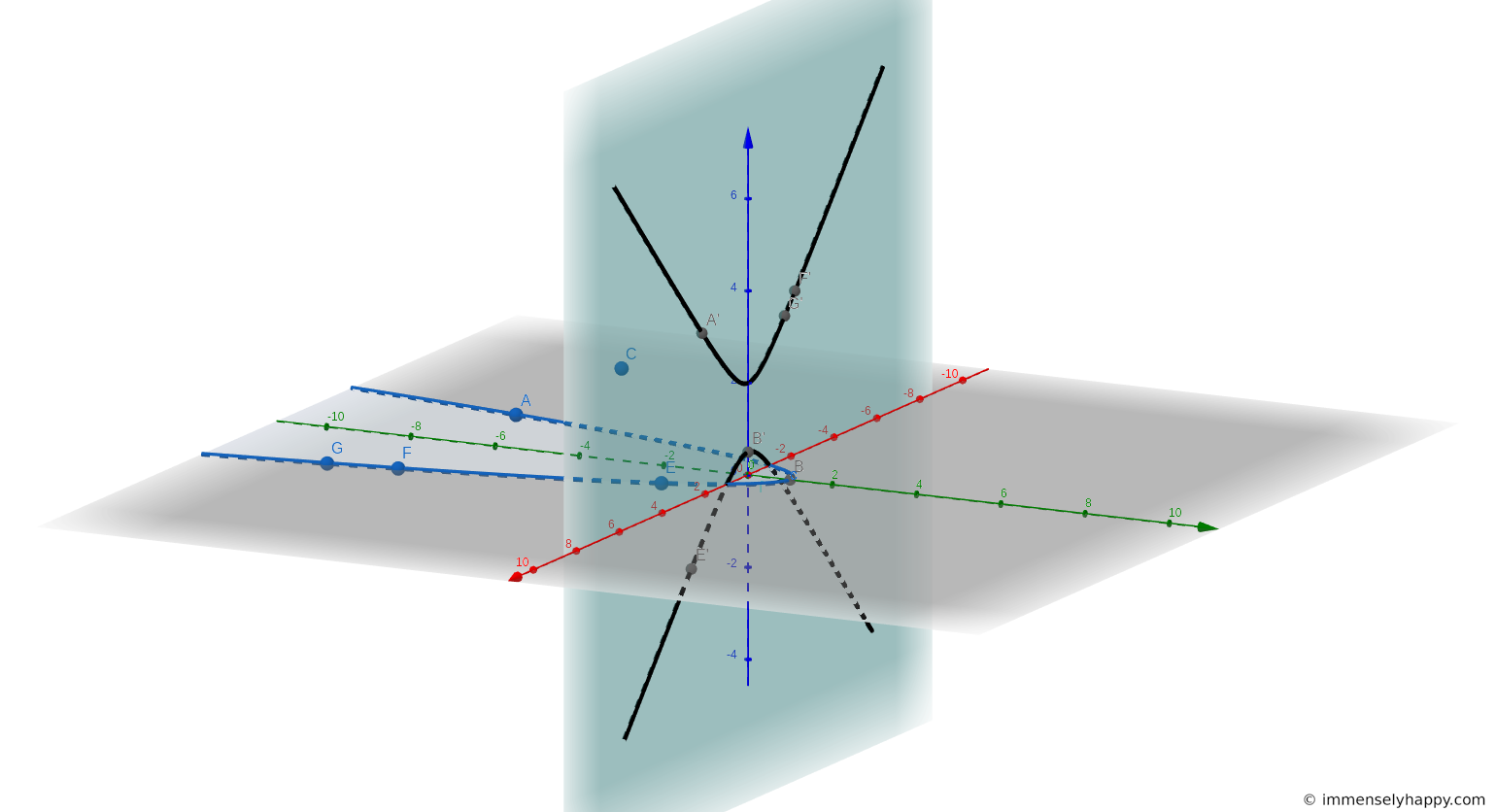

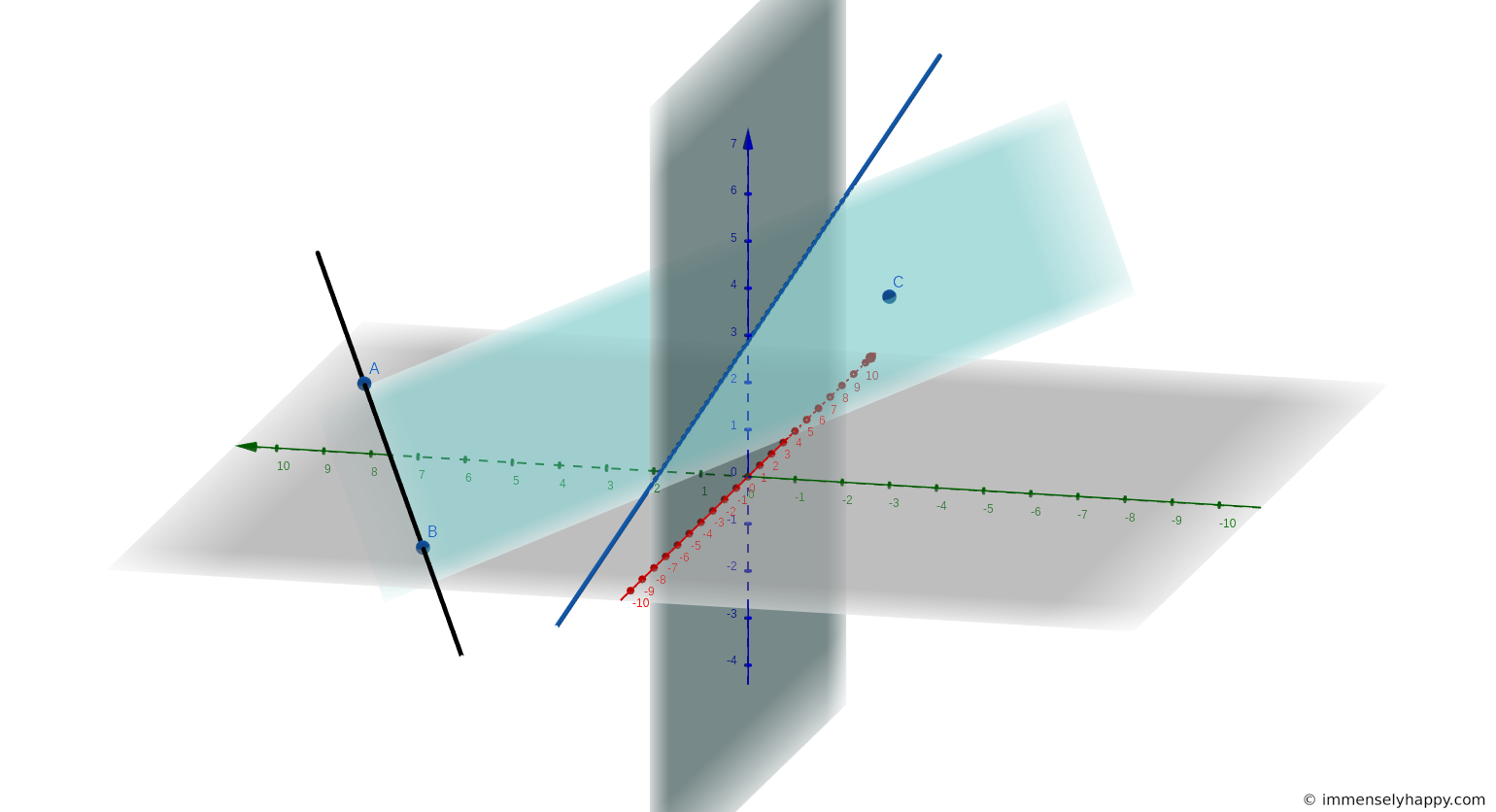

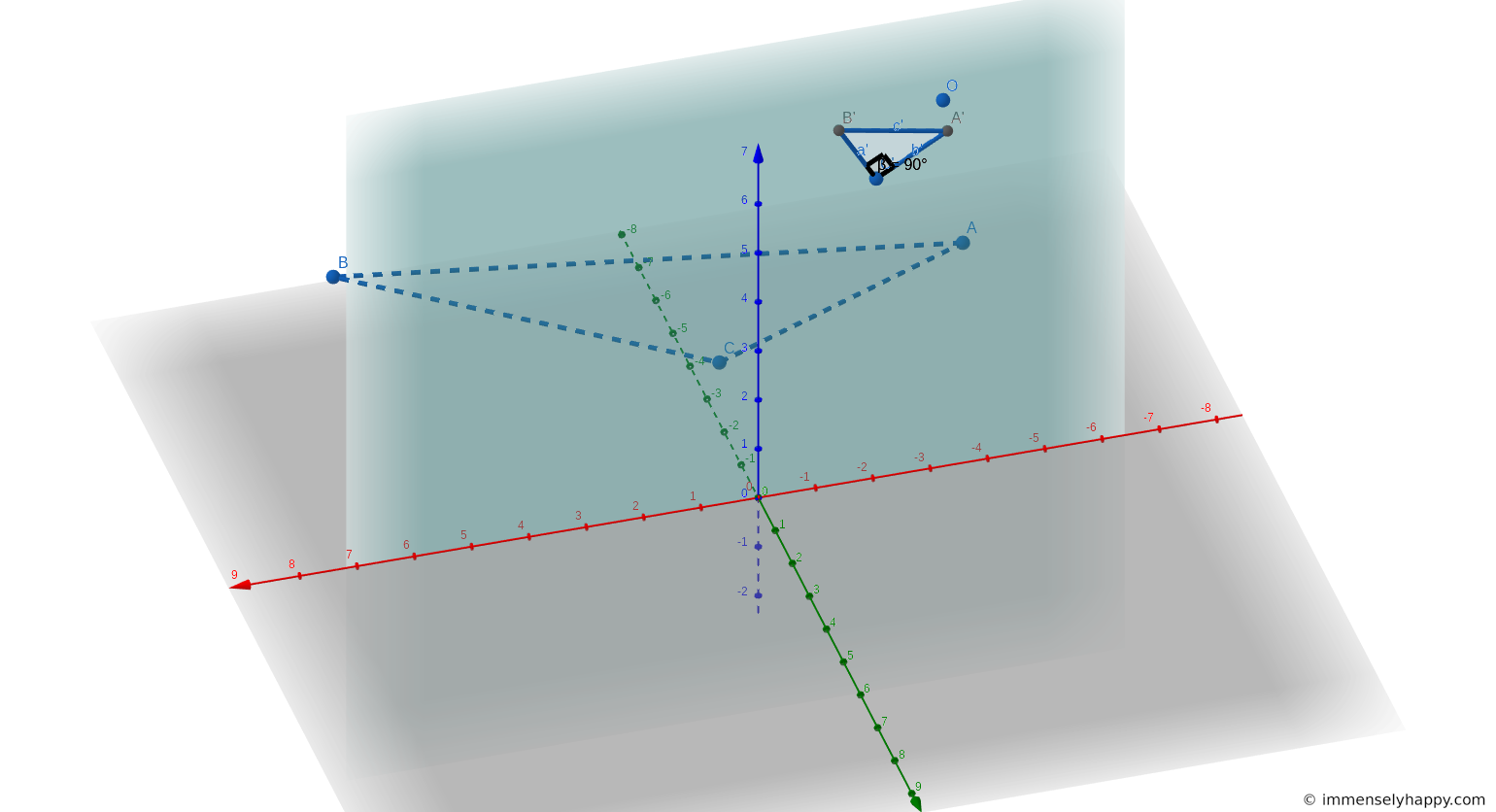

In the figure below, points A, B, D, F & G are not the images of any points in the object plane.

Similarly, consider the line of intersection of the object plane with the plane parallel to the picture plane passing through the viewing point. The projecting line for a point on this line will never intersect with the picture plane. Hence the points on this line will not have an image in the picture plane.

In the figure below, points A, B, D, E, F do not have any images in the picture plane.

9. In a perspective transformation, is a line always represented by a line? Is a non-singular conic always represented by a non-singular conic?

The projecting lines from the viewing point to a line on the object plane extended to infinity on both sides together span an entire plane. The intersection of two planes is a line. So the image of a line under a perspective transformation will always be a line.

The only exception to this case is the line that has no image as we discovered in the solution to exercise 8.

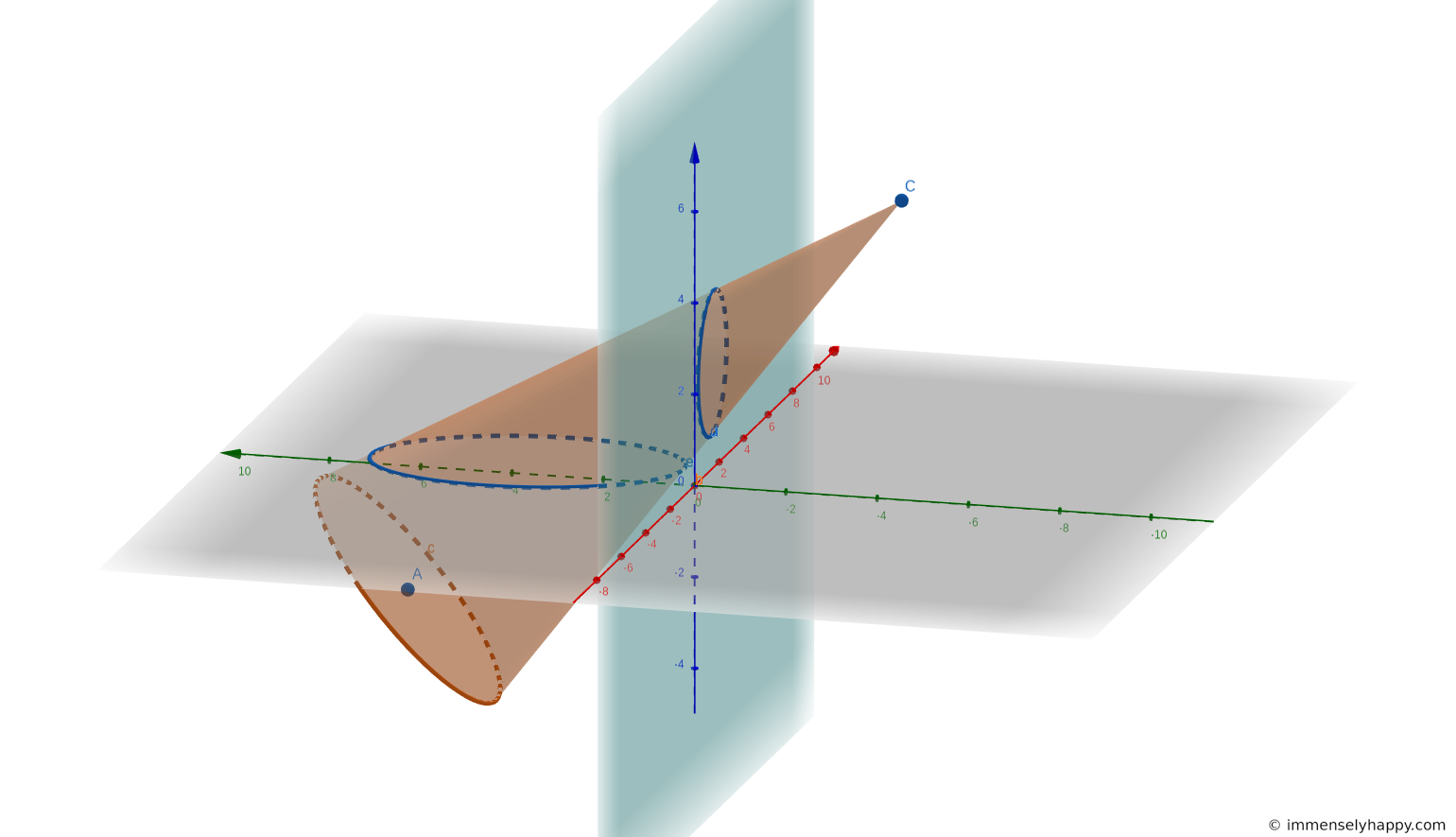

We can look at the perspective projection of conic sections in the following way. The projecting lines from the viewing point to the conic on the object plane form a cone. The intersection of a plane and a cone is by definition a conic section! So the image on the picture plane must be a conic section too.

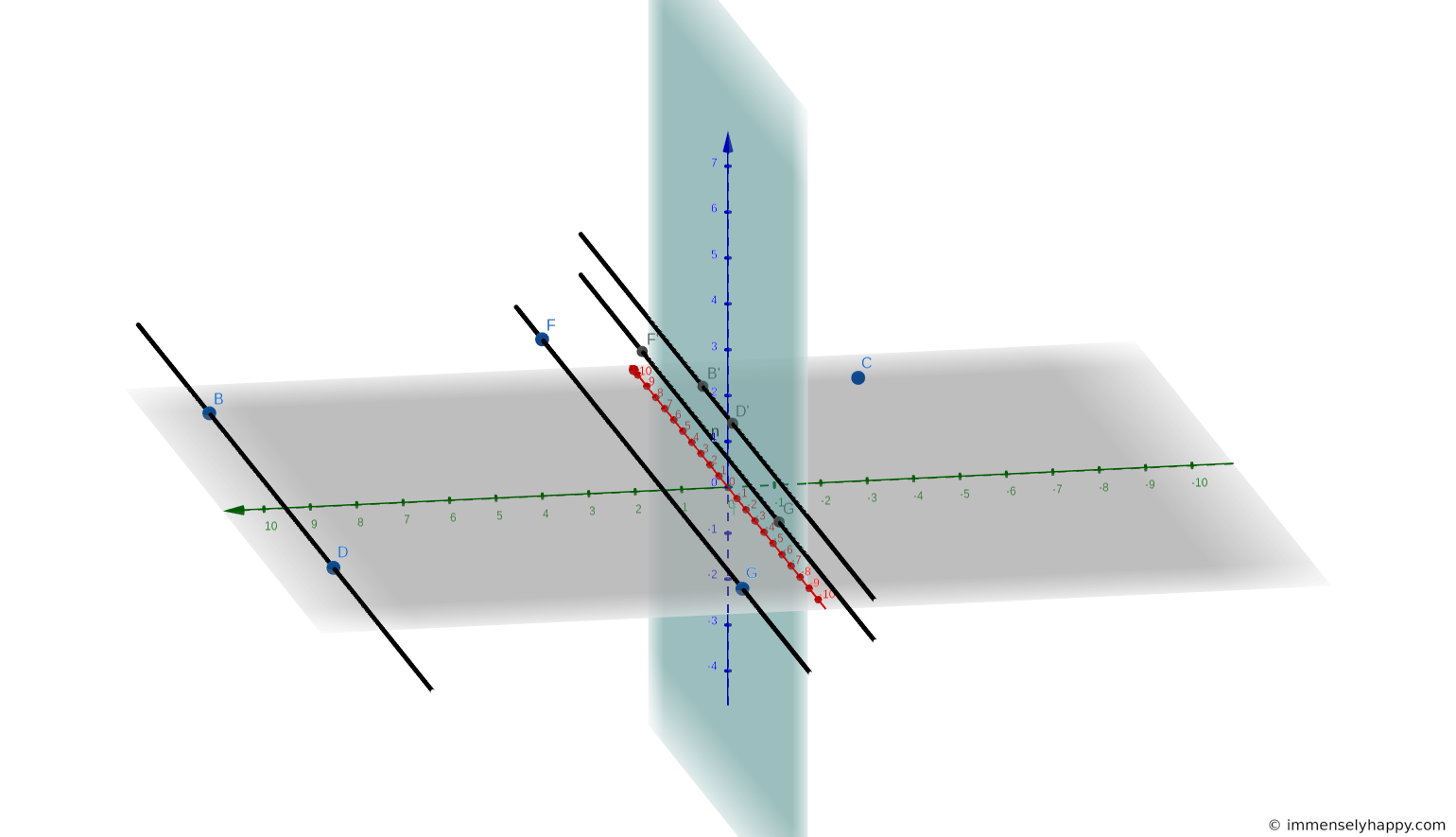

10. In a perspective transformation, are there any parallel lines which are not represented in the picture plane by lines meeting on the vanishing line?

Lines on the object plane that are parallel to the line of intersection of the object and picture plane are transformed into parallel lines that do not meet on the vanishing line.

F’G' and B’D', the images of FG and BD respectively which are parallel to the x-axis, remain parallel to it on the picture plane.

11. In a perspective transformation, is a circle ever represented by a circle?

The logic that is used in the solution here is to make the coefficients of the square terms, and , equal. This is because we know that any quadratic equation in two variables that has the same coefficients for the square terms and does not have the term, is the equation of a circle in the General Cartesian form.

A general circle is represented by a quadratic equation in two variables as follows

The image of this circle under the perspective transformation described in Example 1 will be

This expands to

Now in order to make the coefficients of the square terms equal, we must have

And for the term to be zero, must be zero.

So the circle

is transformed to the circle

by the perspective transformation described in Example 1.

12. In a perspective transformation, is a circle always represented by an ellipse? If not, what other possibilities are there?

Generalizing the solution to the previous question, the image of a circle under the perspective transformation described in Example 1 will be

- an ellipse if 9 - 3b + c > 0

- a parabola if 9 - 3b + c = 0

- a hyperbola if 9 - 3b + c < 0

using the discriminant rule for classifying conics.

So, the image of a circle under a perspective transformation can be an ellipse, a parabola or a hyperbola.

13. What are the possibilities for the image of a parabola under perspective transformation? What are the possibilities for the image of a hyperbola?

We have already proven in problem 9 that the image of a non-singular conic will always be a non-singular conic. So we just need to delineate which conics can be transformed into which other conics.

Consider a general parabola

with . The image of this parabola under the perspective transformation described in Example 1 will be

Expanding this we get

Using the discriminant rule, this will be

- an ellipse if .

- a parabola if .

- a hyperbola if .

So the image of a parabola under perspective transformation has the possibility of being any conic.

The same kind of calculations can be performed for a hyperbola to prove that the image of a hyperbola under perspective transformation has the possibility of being any conic.

14. In a perspective transformation, is a segment always represented by a segment?

By segment I’m assuming the author meant a line segment (as opposed to a segment of a circle).

A line segment is uniquely determined by two points, the start and the end of the segment. If neither of these points lie on the line that has no image (see solution to problem 8), then both of them have an image. In this case, the image of a segment will be a segment.

If either endpoint of the segment lies on the line that has no image then the image of the segment will be a half-open line segment (a line segment that includes only one endpoint). The endpoint that does have an image is the included endpoint and the segment extends to infinity on the other side.

If the segment lies on the line that has no image, then the segment will also not have an image.

15. In a perspective transformation, if is a point between and , is it true that the image of is between the images of and ?

If the point lies on the line that has no image (see the solution to problem 8) then will have no image. In this case, the image of can’t possibly lie between and .

I’ll admit that the proof of the general case had me stumped for a while. After all, it looked so obvious! I had to go back to the fundamentals and look up the theorems related to betweenness of points and lines to get to the solution.

To prove the general case, we can use this theorem of geometry2 that says if A, B, and C are three noncollinear points and if D is a point on the line BC then the point D is between the points B and C if and only if the ray is between the rays AB and AC.

Using this theorem on the perspective transformation of the 3 collinear points 3, we see that the projecting line CP is in between the projecting lines CQ and CR because P is given to be between Q and R. We’ve already established that the image of a line under a perspective transformation is a line and so P', Q' and R' lie on a line. Using the aforementioned theorem one more time, we see that the image P' of P is in between the images Q' and R' because CP' is in between CQ' and CR', which is what we set out to prove.

16. In a perspective transformation, if is a general point in the object plane , and if the viewing point is an arbitrary point , find the coordinates of the image of on the picture plane . What are the equations expressing and in terms of and ?

The equation of the projecting line through and will be

Intersection of the line with the picture plane will give us the coordinates for as

Expressing the object coordinates in terms of the image coordinates we get

We can do a quick check by substituting the values given in Example 1 in these equations and see that we do get the same result for , , and as in the book.

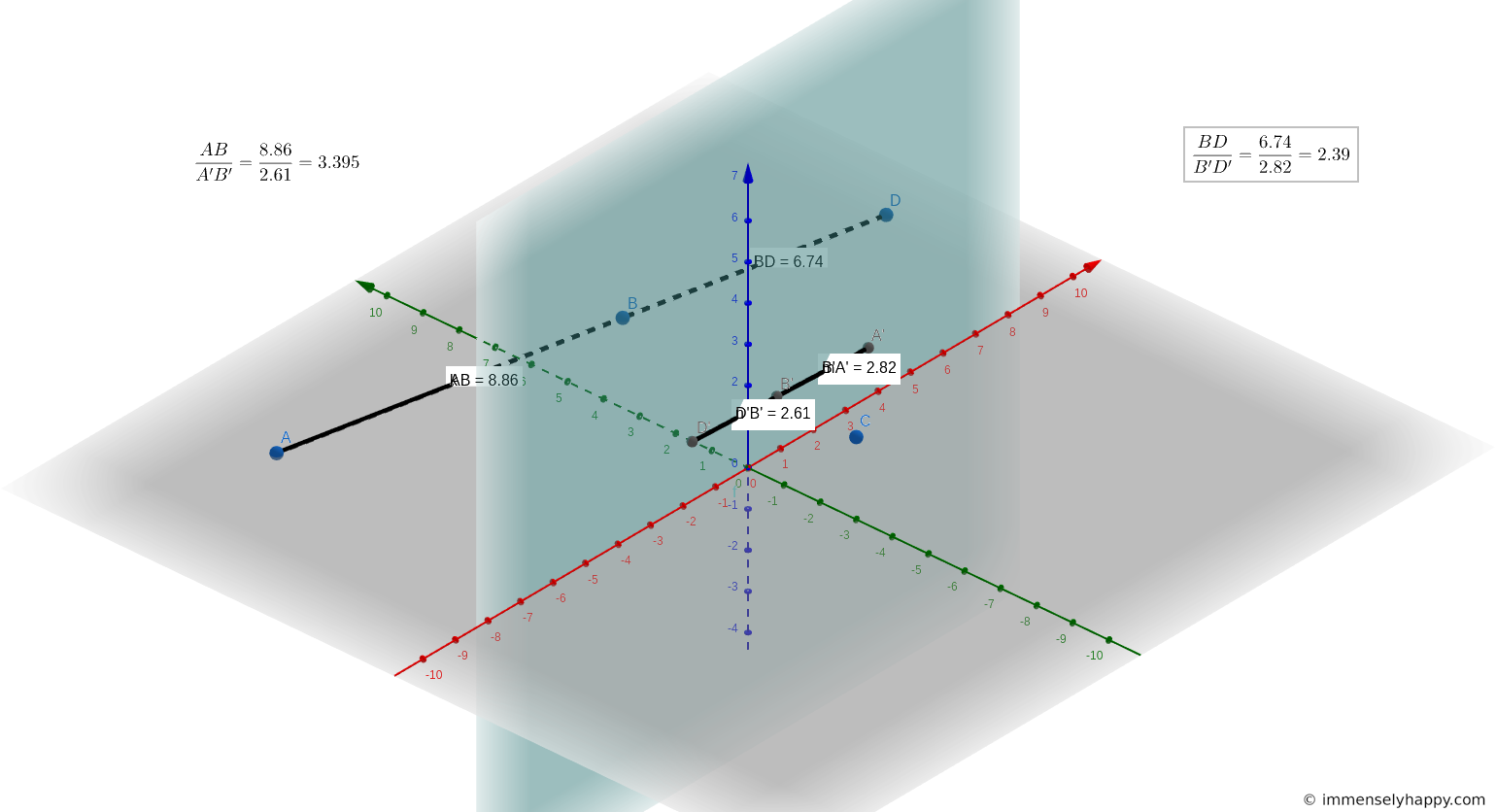

17. In a perspective transformation, are the lengths of all segments altered in the same ratio?

For such questions if we just find one example that contradicts the statement then we’re done.

I will take 3 arbitrary collinear points , and and find their images , and under the perspective transformation described in Example 1.

As you can see

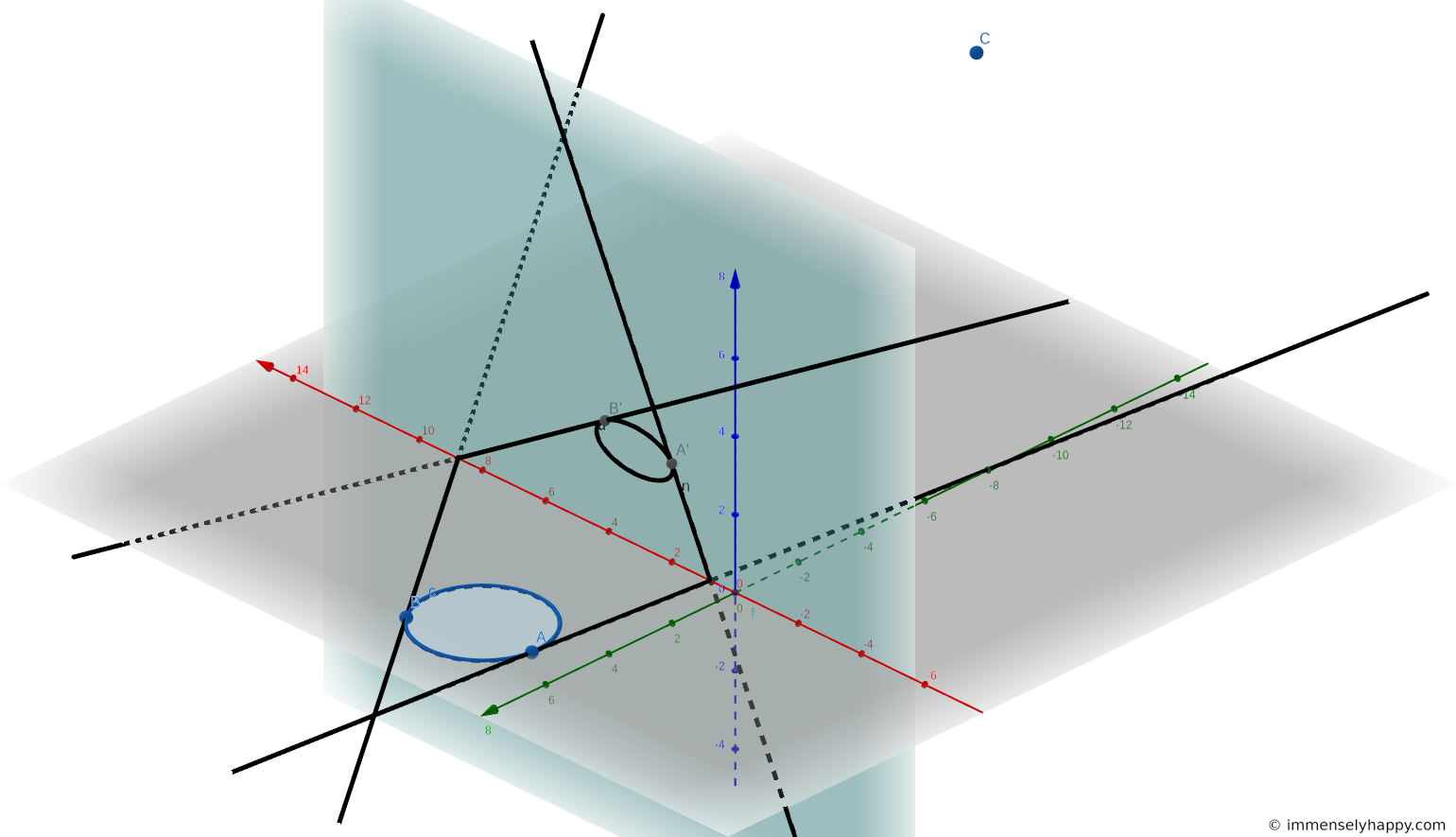

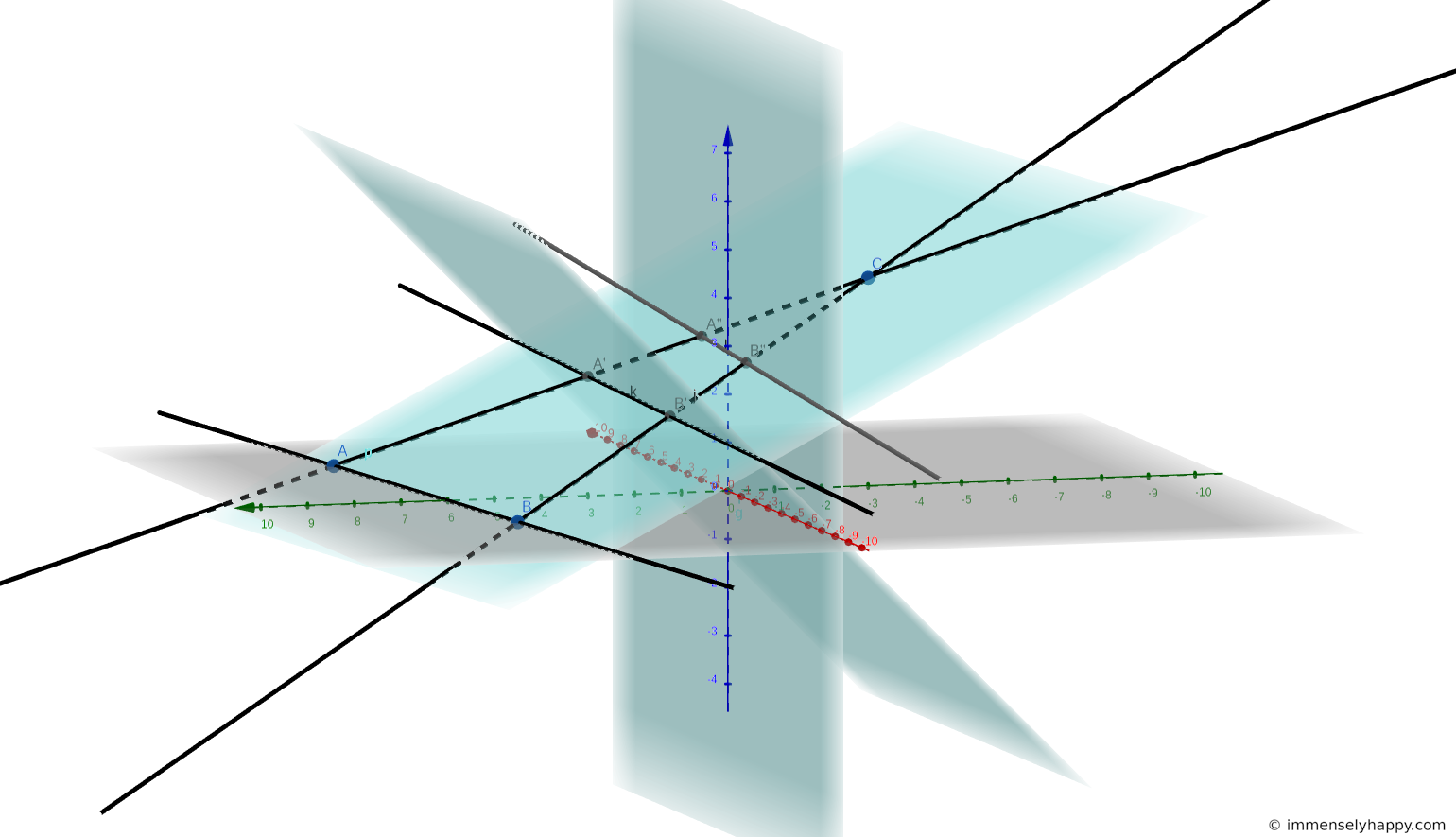

18. In a perspective transformation, is the angle between two lines the same as the angle between the images of the lines?

I’ll employ similar logic here as in the previous solution. We will find one example that contradicts the statement.

Here, I’ve taken three non-collinear points and found their images under the perspective transformation defined in Example 1. Comparing the two angles, we see that

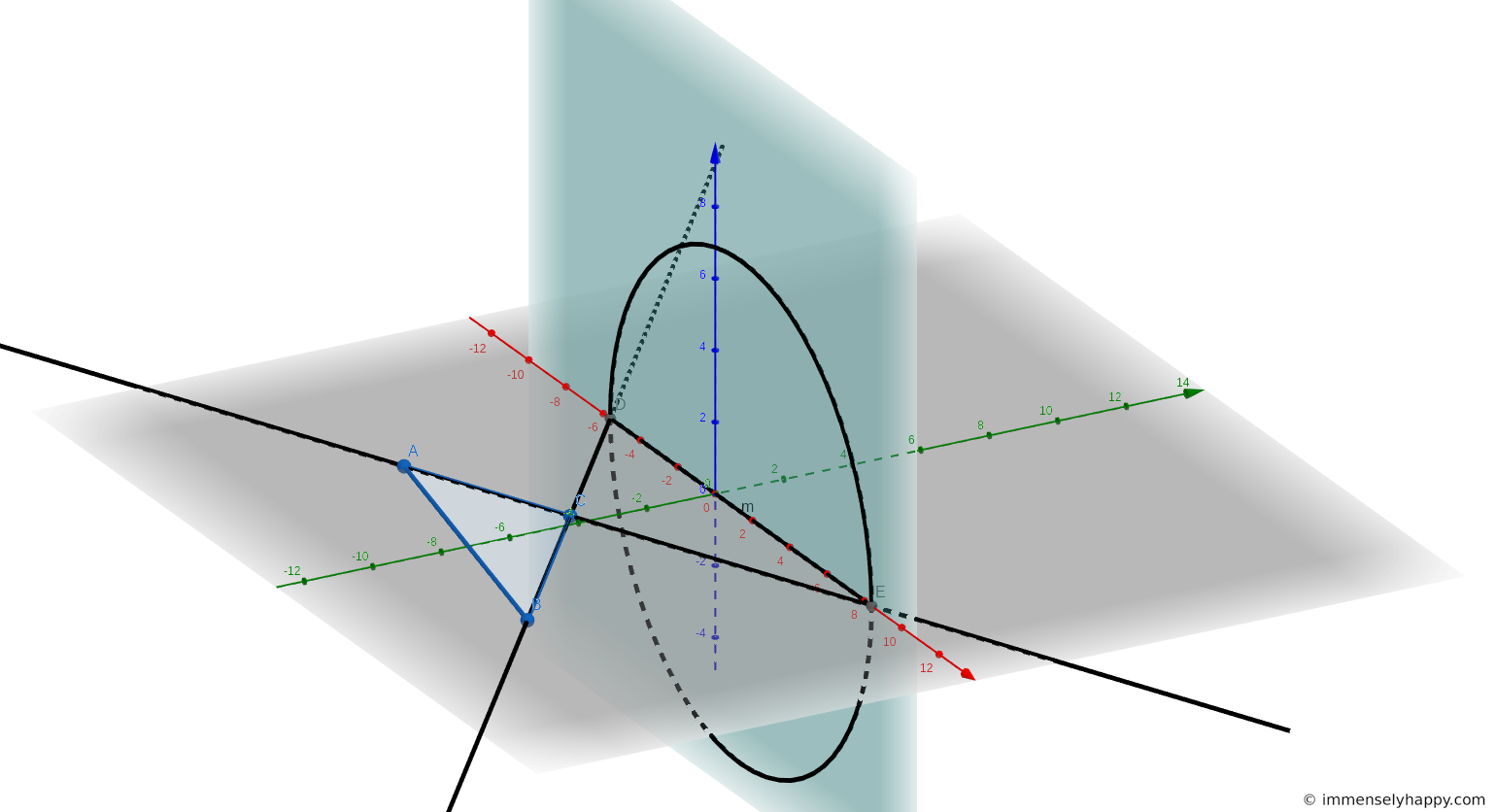

19. In a perspective transformation, if a line is tangent to a circle, is the image of the line tangent to the image of the circle?

We know that a perspective transformation maps points to points (the projecting line that intersects both the object and picture plane meets each plane in exactly one point). This implies that the point of tangency must be mapped to a single point on the picture plane. Now as the point of tangency lies on both the tangent and the circle, its image must also lie on the images of the tangent and the circle.

We can also establish that no two points on one plane are mapped to the same point in the other plane. If this were not true then two projecting lines, that already meet at the viewing point, will meet again at a point in one of the planes, which is not possible as two lines can not intersect in more than one point.

This means that the images of the tangent and the circle can not share any other point other than the point of tangency as the tangent and the circle by definition do not share a point other than the point of tangency in the object plane.

Any line that only shares only one point with a circle is a tangent to the circle (this is not true for a parabola and hence this statement can not be generalized for all conics). Thus, we can rest assured that the image of a tangent to a circle remains tangent to the image of that circle.

In the image below, the points of tangency on the object plane are and , and the points of tangency on the image plane are their images and .

20. In Example 1, verify that for the four collinear points, , , , and the images , , , , the following relation holds.

I’m going to cheat here and use numpy.linalg.norm because, well, I’m really bad at arithmetic and even if I was good, a computer would always be better at it than me.

$$\dfrac{(P_1P_3)(P_2P_4)}{(P_1P_4)(P_2P_3)} = \dfrac{4.24 * 8.49}{9.90

- 2.83} = 1.29$$

The coordinates of the images are , , and

21. If , are four collinear points in the object plane , and if are the images of these points on the image plane under a perspective transformation with center , show that

Let’s consider the four collinear points , , and to lie on the general line

So the four sets of coordinates will be , , , and . Substituting this in the given ratio, we get

We have already established that the image of a line under perspective projection is a line. So the images of the 4 collinear points will also be collinear. We can represent these collinear points as lying on the general line

Using the same logic as above, we get

Expressing the image coordinates in terms of the object coordinates as derived in the solution to exercise 16, we get

$$\dfrac{(P'_1P'_3)(P'_2P'_4)}{(P'_1P'_4)(P'_2P'_3)} = \dfrac{(\dfrac{(am’x_1 + ac' - bx_1)}{(m’x_1 + c' - b)} - \dfrac{(am’x_3 + ac' - bx_3)}{(m’x_3 + c' - b)})(\dfrac{(am’x_2 + ac' - bx_2)}{(m’x_2 + c' - b)} - \dfrac{(am’x_4 + ac' - bx_4)}{(m’x_4 + c' - b)})}{(\dfrac{(am’x_2 + ac' - bx_2)}{(m’x_2 + c' - b)} - \dfrac{(am’x_3 + ac' - bx_3)}{(m’x_3 + c' - b)})(\dfrac{(am’x_1 + ac' - bx_1)}{(m’x_1 + c' - b)} - \dfrac{(am’x_4 + ac'

- bx_4)}{(m’x_4 + c' - b)})}$$

Hence the two ratios are equal.

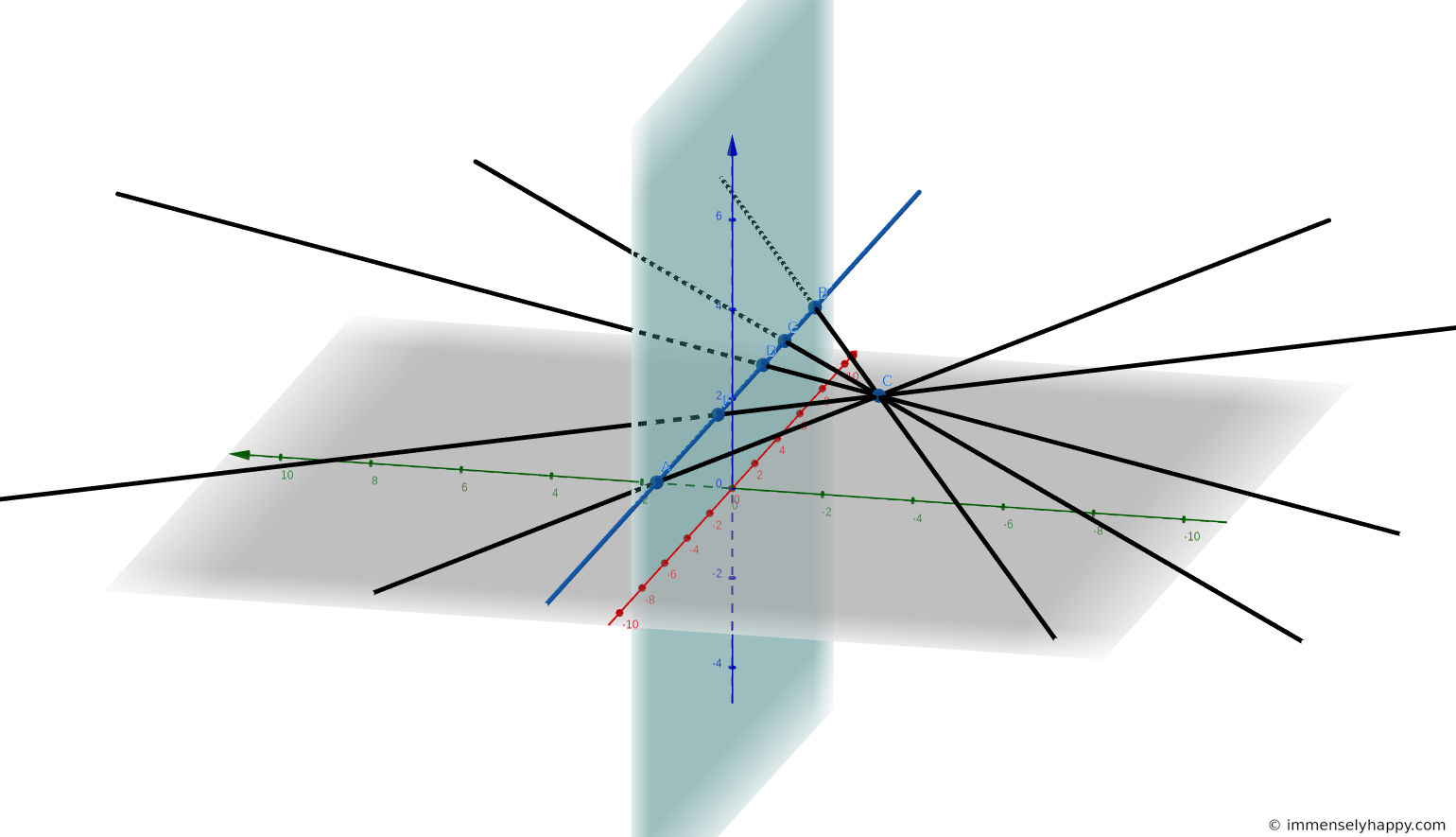

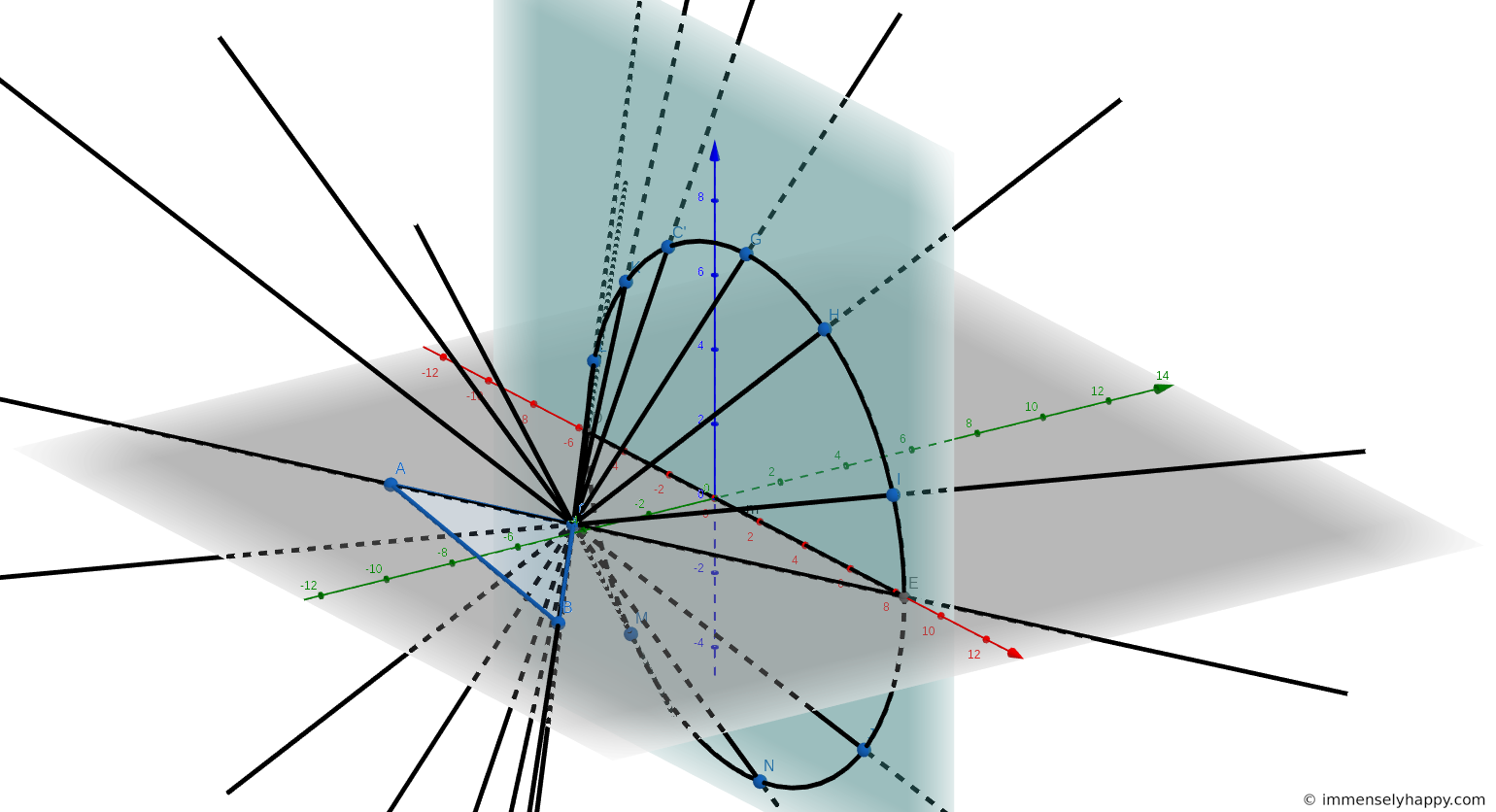

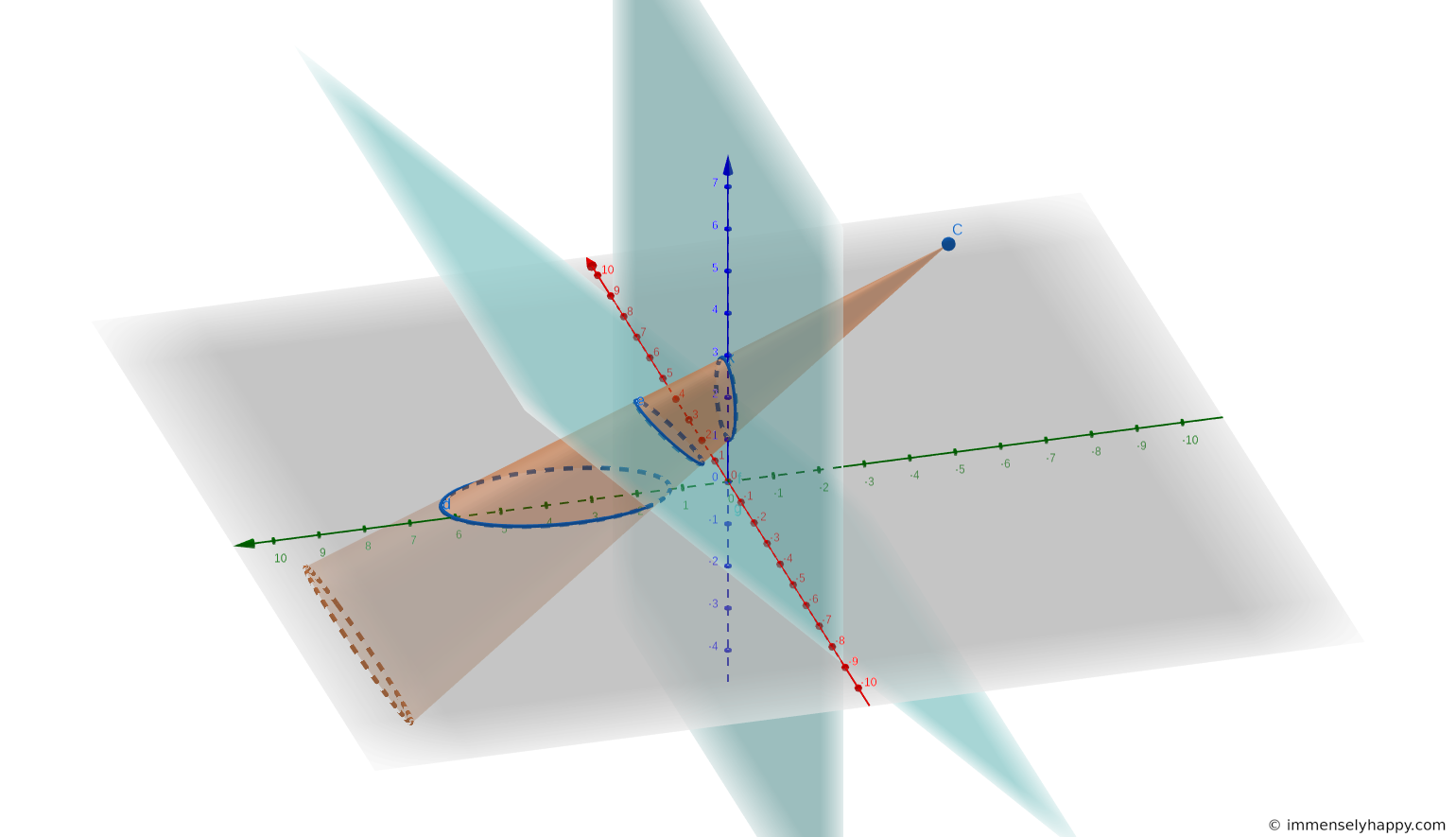

22. Given a triangle in the plane , is it possible to find a viewing point , from which the triangle will appear on the plane as a right triangle?

You certainly are a geometry pro if you got this one straightaway. I managed to solve this only after reading the next two sections.

The key to solving this exercise is to remember that points on the line common to object and image planes are invariant under perspective projection (see the solution to exercise 7).

I’ll explain the logic behind the construction first and then summarize the steps at the end. The construction proceeds by identifying constraints on the points and lines of the image triangle one-by-one to reach the end goal.

Consider the triangle on the object plane. Let’s say we want to transform to a right angle. It is helpful for the purpose of this solution to think of the sides of the triangle as lines rather than line segments. In other words, we want the images and of the two lines and must form a right angle.

Let’s think about the image of a line under perspective transformation in general. The image of a line must pass through the intersection of and the line common to the object and image plane (the x-axis in this case), provided they intersect. This means for any line, we know at least one point that lies on the image of the line.

So, the first constraint we discovered is that one point each, on the images of the two sides of the triangle, are fixed. We must now find the direction of the lines through these points so that they meet at a right angle.

One way I know of to construct a right angle between two given points is to construct a circle with the two points lying on opposite ends of the diameter. We also know that the angle inscribed in a semi-circle is always going to be a right angle. So I’ll find the intersection of and with the x-axis as and and draw a circle with the diameter being . Any point, on this the circle will form a right angle with and .

It is important to remember that and are not images of and . They are points on the image lines and . What we have ensured thus far is that the images of the lines and will meet at right angles if the image of lies on the circle.

If we find a way to constrain the image of to fall on this circle, then we’re done.

How do we make the image of lie on the circle? Connect and a point (its intended image) on the circle, with a line. Now any point on this line, when taken as the viewing point, will result in the image of being the chosen on the circle. As this construction will work equally well for any point on the circle, we get a double cone of possibilities! Any point on the double cone with apex at C and the circle as the directrix can be chosen as the viewing point to get a point on the circle to be the image of .

As the image of C falls on the circle, the angle between and is guaranteed to be a right angle.

Here is the summary of the algorithm for this construction.

- Find the intersection of any two sides of the triangle with the line common to the object and picture planes. If one of the sides is parallel to this line then use the other side. More than one side of a triangle can’t be parallel to the same line.

- Draw a segment with these intersections as endpoints.

- Draw a circle with the segment constructed in #2 as its diameter.

- Draw a double cone with the vertex common to both sides of the triangle as the apex of the cone and the circle constructed in #3 as its directrix. (w.r.t to the image: that’s the best I could do to draw an oblique cone in GeoGebra.)

- Choose any point on this double cone to be the viewing point.

The image of the triangle under this construction will be a right triangle.

23. Answer Exercise 22 if it is required that the image of the given triangle be isosceles.

This is another interesting one. The solution is in the same vein as the answer to the previous question. The only additional piece you will need is to know how to find the locus of points at which two given points subtend a particular angle.

If the angle is a right angle, we can construct a circle with the two points on the diameter as in the previous exercise. What if the angle is ? What about ? I still think it’s a circle/arc, but what are the parameters of this circle? Let’s try to figure it out.

We know that the angle subtended at the center by any two points on a circle is twice the angle subtended at any other point on the circle by the same two points. So if we settle on a particular angle, say , then all we need to do is find the radius of the circle for which the given pair of points subtend an angle of at the center.

Given the length of a chord and the angle it subtends at the center, we can find the radius of the circle that contains this chord using trigonometry as shown below. Here is the radius. Note that because the radius that is perpendicular to a chord also bisects the chord.

Thus, the locus of the points at which two given points, and , subtend an angle is the major arc of the circle that subtends an angle of at the center. If the angle is then the chord becomes the diameter (as it subtends at the center) and the arc becomes the whole circle!

So, the steps of the algorithm to achieve a construction in which an arbitrary triangle is transformed to an isosceles triangle under perspective projection are as follows.

- Find the points of intersection of , , and with the line common to the object and picture plane (x-axis in this case). Let’s call them , , respectively.

- Choose the value of the two equal angles of the final isosceles triangle. Let’s call the chosen angle .

- Construct two circles, one in which and subtend at the center, and another in which and subtend at the center using steps explained above.

- Draw two double cones, one with apex at and directrix as the circle containing and the other with apex at and directrix as the circle containing . From each cone remove the portion that is attached to the minor arc of each directrix. Let’s call the modified cones and .

- Chose any point on the intersection of and to be the viewing point.

The image of the triangle under this construction will be an isosceles triangle with two angles measuring .

Note: If you don’t remove the portion attached to the minor arc of the cone, you might get one angle to be instead of as that’s the angle the chord subtends in the minor arc.

24. Answer Exercise 22 if it is required that the image of the given triangle be equilateral.

Just chose to be and follow the steps outlined in the solution to the previous exercise.

25. Discuss the perspective transformation when the object plane is not perpendicular to the picture plane.

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned about perspective transformation when the object and picture planes are perpendicular. This way we can evaluate the case when they are not perpendicular in relation to when they are.

Under a perspective transformation, when the object and picture plane are perpendicular, we can observe the following facts.

- There’s a one-to-one mapping between points on the object plane and the points on the picture plane except for points on the two lines discussed in the solution to problem 8. The same goes for lines. Lines map to lines except for the two lines discussed in the solution to problem 8.

- Parallel lines on the object plane (that are not parallel to the line common to the object and picture plane) are transformed into lines that meet at a point in the picture plane.

- Points on the line common to the object and picture plane coincide with their images.

- Non-degenerate conics on the object plane always map to non-degenerate conics on the picture plane.

- If then unless the point does not have an image at all.

- .

- Angles, ratios, shape and distance are not preserved.

- A line segment is mapped to a line segment if and only if both endpoints are not on the line that has no image.

- Tangency to an ellipse is preserved if the tangent has an image.

We can verify that all these properties hold true even when the object and picture plane are not perpendicular to each other by following the same process as we did when the planes were perpendicular. Below I’ve highlighted some of the facts that I consider important.

References

-

Wikipedia. Conic Section. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conic_section. ↩︎

-

Theorem 3.3.10. Gerard A. Venema. (2006), Foundations of Geometry, Pearson. ↩︎

-

means the point is in between points and . ↩︎